One Man Nutcracker & Year in Review (Pt 1)

A surprisingly moving holiday show, plus a note on year end appeals

Welcome to Plays Unpleasant #4!

A big thank you to all of my subscribers! I hope you’ve all made it through, and maybe even experienced joy, the holiday season. I’m feeling pretty good about 2024, very grateful for your support, and mystified by the Mummer’s parade. Why is it so long? Get it together, Mummers! Y’all need more stage managers.

If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can make both my and your 2024 better by pressing that pretty little button:

And if you’re already subscribed, you can give me the gift of telling your friends, and give your friends the gift of this blog:

This will be the first of a few entries looking back on the year that was, but first! a holiday show!

One Man Nutcracker

On New Year’s Eve, I went to the Drake at noon to see Chris Davis’ final performance of his holiday show. But it’s not about Christmas, it’s about the Nutcracker. And it’s a biting love letter to the Nutcracker, to ballet, and, dare I say, to theatrical performance itself. It's a celebration of amateurism, of magic, of the very venture of theater. It's a small marvel. Very funny, charming, and clever. It’s stupid and it’s smart. I don't love everything in it—some of the framing devices up front and a cliche here or there, but the storytelling works. A voiceover narration kind of comes and goes, but I’m too busy loving the show to care. Chief among cliches for me is a a red pill/blue pill moment, but it does it’s job to stage the choice of taking on this endeavor.

Having taken the red pill (opened the red envelope containing a script, which is also paradoxically by him? Wonderful stuff), Davis exclaims “One man Nutcracker? That's impossible!” setting up the task ahead for himself. Isn’t that the task of every actor, doing the impossible, being someone else for a while to make some people feel something? The task of the theater, this insane thing we pursue because we love it. And it's all of our task. Faced with the “gordian knot of existence,” how do any of us do it? By celebrating the things we love, together, even if they're problematic. Happy New Year, everyone.

(Apologies to Chris for a write-up after closing, but I look forward to seeing it again next year)

Year End Appeals

The inbox flood of generic fundraising emails that began on the Tuesday after Thanksgiving has finally concluded following the last minute flourish of the 31st. How many did you get? How many did you open? I’m not sure that the consistent begging is a good holiday look, but I am sure the implication that “Theater is a tax write off!” is not a great justification for the continued existence of our institutions.

That seemingly every theater does this every year says a lot about the audience—who is making enough, and has enough deductions to get over the $14k standard deduction, to get those tax benefits? Not me. But this isn’t just a thing about branding, performing arts institutions send me more physical mail than anyone else. Not every theater does all this. Maybe those are the ones most worth paying attention to (at least they respect that your attention is valuable). But why is everyone else flooding my mailbox and my inbox? And those mailings are not cheap, which presumably means they have a solid return on the investment, which, to beat a dead horse, says a lot about the base of the theater.

Some unsolicited advice: send fewer appeals, that will make what you send more meaningful.

Looking Back, Part 1

Starting chronologically, my year in the arts began on January 10th when I went to see Avatar 2 on discount day. This isn’t a film blog (follow me on Letterboxd), but folks, The Way of the Water is great. James Cameron doesn’t miss. How often do you see a major mainstream smash that’s both an immersive love letter to the majesty of the natural world and a critique of nonviolent resistance? Never before (did someone show it to the orcas1?).

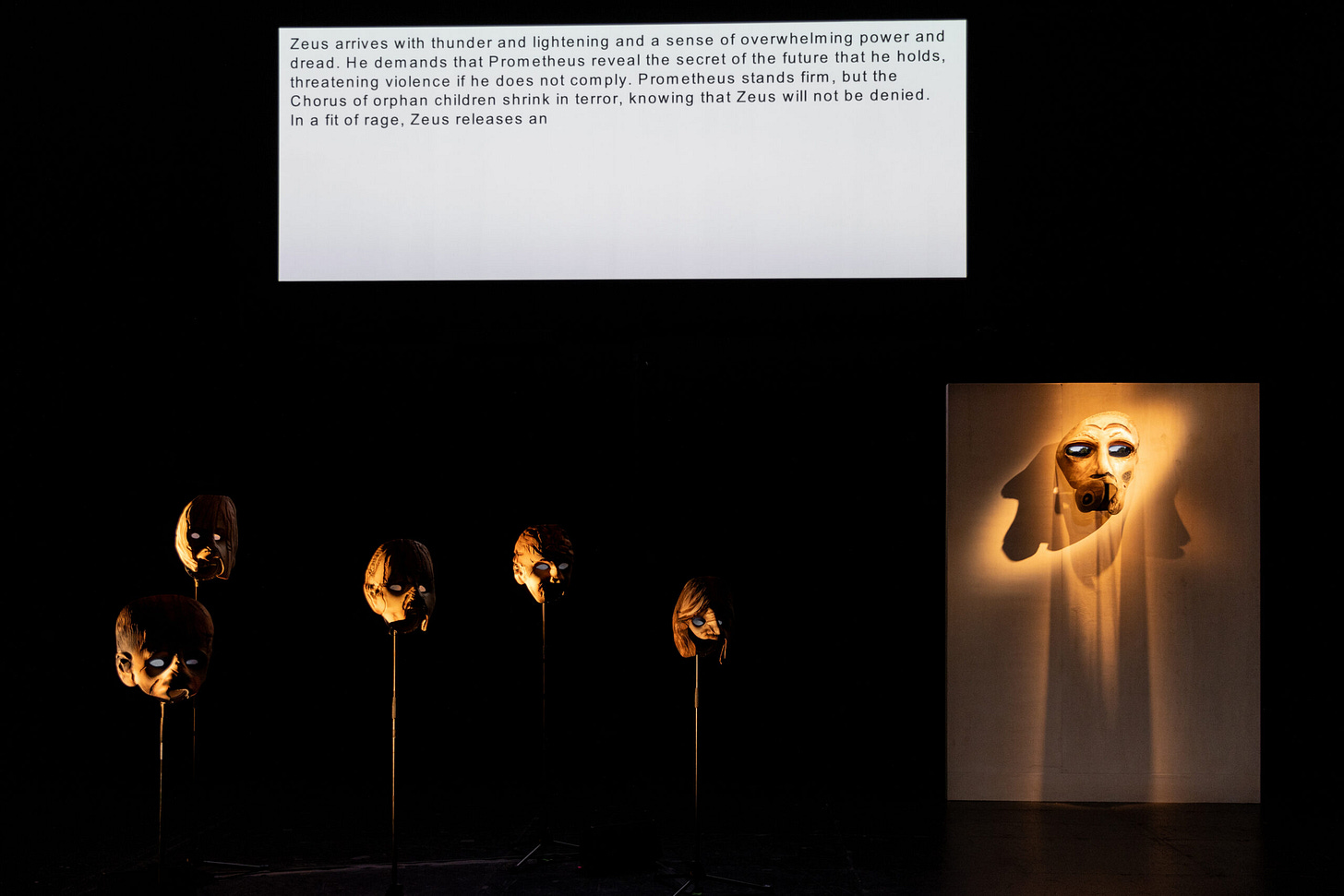

I then saw the world premier, or what was really a workshop maybe, of Annie Dorsen’s Prometheus (Working Title) at Bryn Mawr, which went on to show at Theater for a New Audience as Prometheus Firebringer. I didn’t go see it in New York, it was billed as a world premiere here rather than a workshop, so I don’t know what was changed in the intervening months if anything, but this show, pardon my language, is not a successful evening of theater. A generative algorithm is programmed to recreate for us the lost Aeschylus play Prometheus the Fire Bringer, text which is then delivered to the audience via other algorithms. The GPT-3 generated text just isn’t compelling, and that seems to be part of Dorsen’s point, although it would also seem to run contra to her entire previous body of algorithmic work.

I also think Dorsen’s lecture, assembled from quotes of other texts (and cited live on a screen behind her) and constructed as a compare-and-contrast with the masks on a stick with screens for eyes on the other side of the stage, is also fairly thin. It’s more invested in trying to be clever, including citations for words like “the,” rather than making an impact as either a monologue or as serious media criticism. I get the structure is the point, but the speech just isn’t that insightful. And there’s no movement, in fact, there’s even less movement than in a normal lecture, as Dorsen is seated as she reads. And, well, it’s a lecture.

I believe I’ve seen the entirety of Annie Dorsen’s theatrical algorithmic body of work, in at least some iteration, and I’m comfortable saying almost all of it is boring and not aging well. If you’ve ever interacted with a chatbot, you might as well have seen Hello Hi There. This stuff is very much a product of its brief moment in time, and they’re interesting as archival pieces and as intellectual exercises, though I will grant that they could be fairly successful as installations rather than as evening-length performances. If Dorsen is working out a critique of algorithmic technologies, her work suffers by always trailing these technologies. If her critique of large language models was novel when it was first conceived, it’s now a well worn one that we’re all confronted with. Even one point that is rendered completely obvious in the piece, that the texts these things generate are ultimately junk, is well known to anyone who is seriously looking at them.

The exceptions are pieces of her algorithmic Hamlet (A Piece of Work), and Yesterday Tomorrow, which at times is really something, as the singers follow along as the machine rewrites the Beatles’ Yesterday into Annie’s Tomorrow. All of this is to say what is now obvious if you’re paying attention to how so-called AI works: generative algorithms are limited entirely by their inputs and what they’re trained on. Dorsen’s work, at its best, reveals the hand of the author and makes those inputs clear, but that doesn’t always make for compelling theater.

With Prometheus, Dorsen seems to be addressing some of these elephants in the room about AI generated art, but it fails to address the biggest one of all: that generative algorithms are based on one of the largest acts of intellectual property theft ever committed. But not only did someone have to create those datasets, someone had to write the algorithm, and the machines that run them consume huge quantities of resources.

There’s also another elephant in the room: these technologies (like many before them over the last two decades) don’t deliver on their promise and probably never will, at least not without either upending copyright law entirely, supplementing it with massive quantities of human labor, or both. The perception that they are, or will become, broadly useful technologies is something there’s a lot of investment in maintaining, but that could drop at any moment (like the Metaverse, which was everything until it was nothing). That’s not to say that generative AI doesn’t pose a lot of threats to creative labor, it does! But those threats aren’t necessarily the threats we’re being warned about.

Dorsen is very talented, accomplished, and smart. Though she’s plainly stated concerns over these deeper issues, they don’t show up in the shows where the critiques are working at surface levels. This is perhaps one of the reasons her work is so successful at capturing our imaginations and the imaginations of funders (Dorsen received a MacArthur grant in 2019). The more serious questions about generative algorithms aren’t merely about them as tools, but how the structural forces shaping, building, deploying, and selling them.

Next week I’ll look back at The Wilma’s gender-fucked Twelfth Night. But having already mentioned a movie, I’d be remiss to move on from January without a shoutout to the Philadelphia Film Society for screening the very weird, very queer, and very cease-and-desisted The People’s Joker.

Upcoming:

I’m excited for Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me, the new Wooster Group x Eric Berryman joint at the Performing Garage in New York. This is another entry in their series of vinyl record shows, with actors performing, or channeling, the album (the Wooster Group’s re-performance of recorded media is consistently fascinating, turning the actor into a medium in so many senses). Berryman is a powerhouse, and here he performs alongside a drummer. Get You're Ass… takes on another of folklorist Bruce Jackson’s field recordings, as seen in The Wooster’s The B-Side, which showed as part of the 2019 curated Fringe. Opens January 11th and runs through February 3rd.

Under the Radar is also back, apparently, including with John Jarboe’s deeply uneven Rose: You Are What You Eat at La Mama, opening on the 10th. Rose premiered as part of the curated Fringe (more on this later in the year-in-review). As much as I want to support Philly artists on tour, I am afraid that New York audiences will not treat this one kindly.

Locally, Samuel D. Hunter’s (author of the deeply problematic The Whale) A Case for the Exsistence of God enters previews at Theater Exile tomorrow and opens next Thursday the 11th. I question the wisdom of having 1/3rd of an initial run be previews, but this is the American theater, and nothing makes sense here. The two-hander won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award and features Keith Conallen and Isaiah Caleb Stanley.

I bet you didn’t expect a tie in to the Mummers parade here.